Friends don't let friends pay in yuan

Recent U.S. sanctions have made life much more difficult for Russian importers: Chinese banks don't want their money. Paying in yuan, once touted as the best answer to sanctions, is no solution.

Reuters recently reported that Russian and Chinese companies are discussing barter deals in agriculture. What may sound like yet another sign of ever-closer cooperation between Russia and China is actually quite the opposite. When someone discusses barter trade, it is a sure sign that something is not working in the bilateral economic relationship.

There is a reason why barter deals are a rare exception in modern trade. They are extremely cumbersome to set up, because they usually involve more than two parties whose interests must be perfectly aligned at any given time. They are inflexible, because if you are paid in goods, you are stuck with those goods and cannot easily change your mind. They can be a logistical nightmare.

Sometimes countries barter when they run out of hard currency. But Russia seems to have plenty of hard currency to pay with. Instead, Moscow has another problem: Russian money is tainted with sanctions risk. Most foreign banks don't want to process payments from Russia because they can never be sure that a given payment is not linked to sanctions evasion. Unfortunately for these banks and their compliance departments, the very idea of sanctions evasion is to disguise illegal transanctions as legal transactions, which means that even if a bank does its expensive and time-consuming research on a client, big risks remain. This is why the Russian circumvention trade taints all Russian transactions in the eyes of foreign banks.

Until late 2023, Russia seemed to have successfully adapted to the reality of financial sanctions. Using a combination of dollars, yuan, and rubles to settle trade meant that paying for imports wasn't usually a major headache. That changed in December 2023, when U.S. President signed an executive order threatening secondary sanctions against foreign banks that facilitate transactions with Russia's military-industrial complex. In June 2024, the Moscow Exchange was sanctioned, expanding the scope of the December sanctions.

Since then, there have been more and more reports about major payment problems, especially for Russian importers. Vazhnye Istorii (VI) published a long-read on the issue on August 15. It describes how complex it has become for any Russian company to send a payment anywhere abroad. 70% of Russian importers and 30% of Russian exporters now rely on specialized agents to settle payments with foreign partners, one of VI's sources estimates. Russian companies are desperately looking for banks in China that are still willing to accept their "Russian" yuan, but if they are trading goods that could be linked to military use - even if it takes a lot of imagination - Chinese banks don't want yuan payments from Russia.

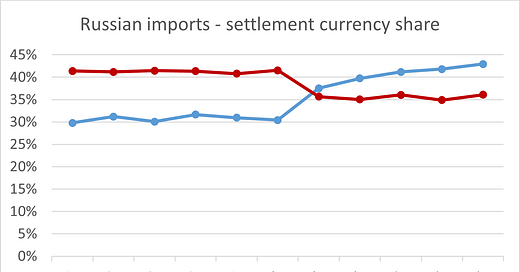

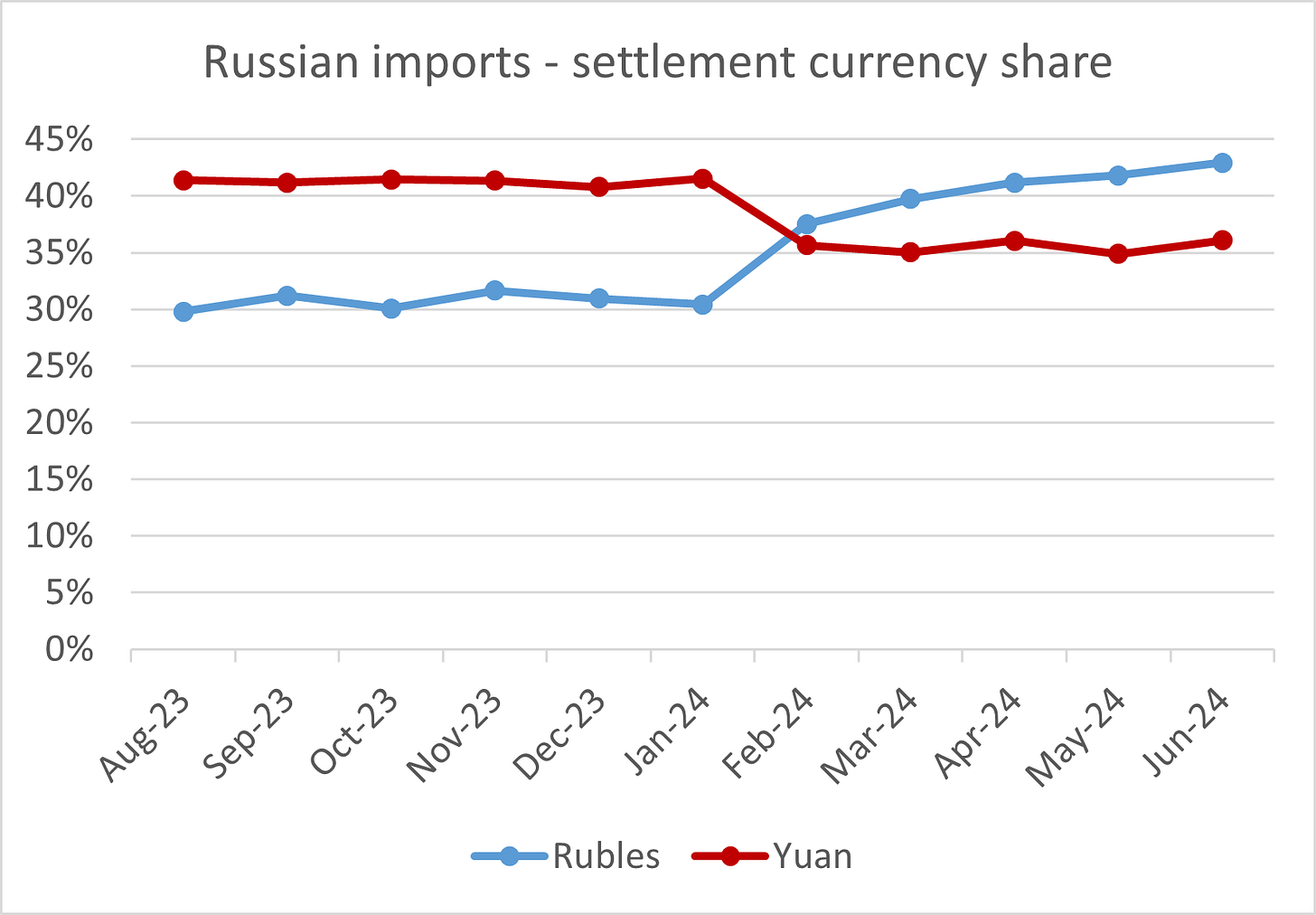

The statistics of Russia’s Central Bank seem to support the reports about payment issues in Chinese currencies (see chart above). Earlier in 2024, they show a certain decrease in the share of Russian imports that are settled in yuan (more precisely: Yuan and other non-Western currencies - but this is almost all yuan). Meanwhile, the share of settlements in rubles is increasing. This is most likely due to two-stage payment schemes, as Alex Isakov from Bloomberg suggests: Russian companies pay rubles to an agent (perhaps in one of Russia's neighboring countries), and this agent pays the business partner abroad in "clean" currency. I recently stumbled upon an advertisement from one of these agents on a Russian telegram channel for importers.

Of course, these agents are not free. According to VI, their services increase the effective price of imports by 6-30%, depending on “how intensively sanctioned” a certain imported good is. These costs could be passed on to Russian consumers, worsening Russia’s inflation problem. In monthly inflation figures for non-food items, there are no clear signs of this problem yet. Prices on non-food items (such as consumer goods imports) grew slower in July (4.3% from June, seasonally adjusted, annualized) than overall inflation, if the increase of gasoline prices is excluded, the Central Bank reported. But price increases in imports could be hidden behind changes in the exchange rate (the ruble was strengthening recently, at least until Ukraine’s Kursk operation) or they could come with a delay.

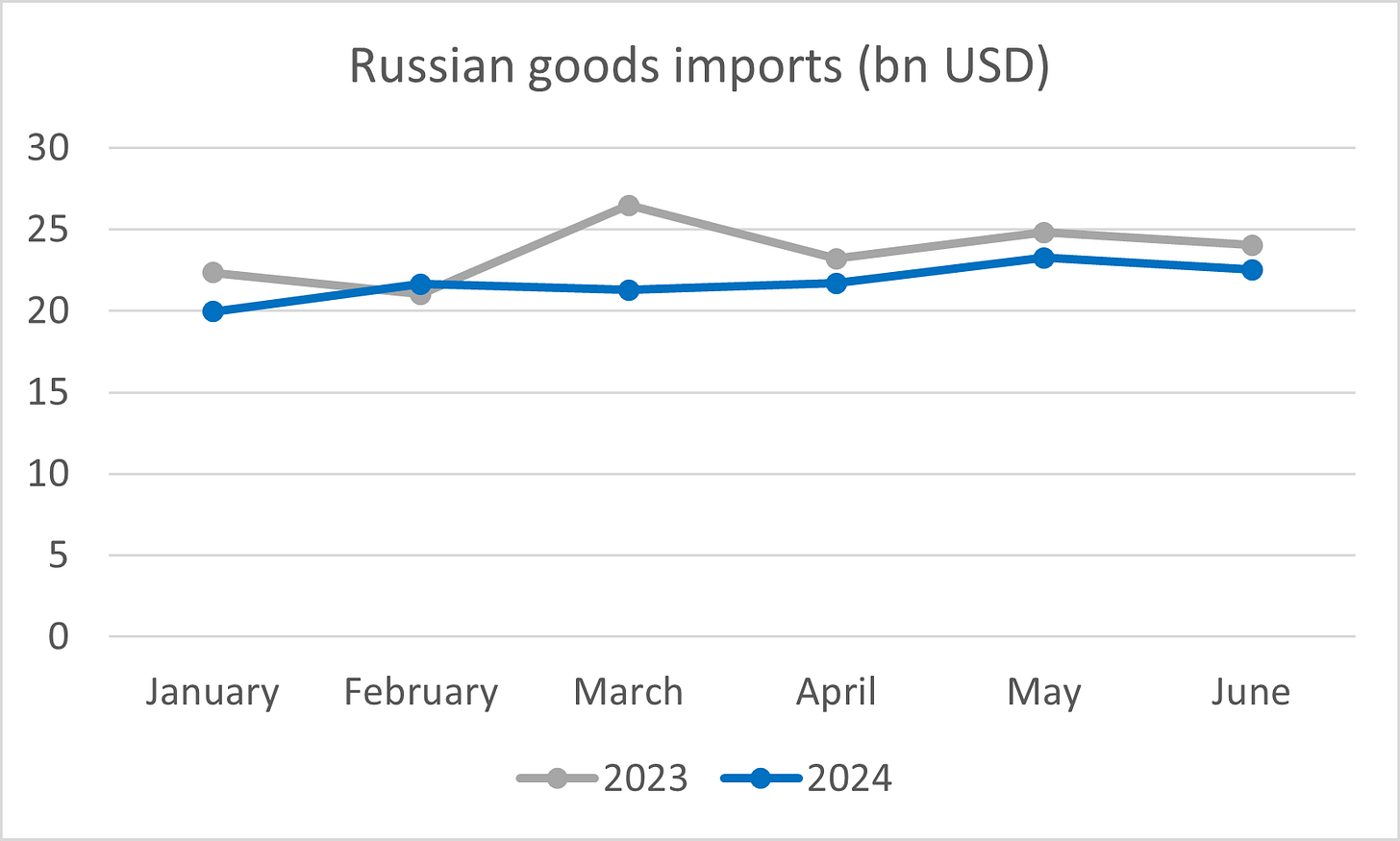

There is also no significant change yet in the dollar value of Russian imports, as reported by Russian customs (chart above), and no change in Russian imports from China, as reported by Chinese customs. A slight decline in total imports compared to last year is likely related to cooling demand in Russia as a result of very high interest rates in Russia. However, there are dramatic shifts in certain types of imports. For example, Kommersant reports that imports of Intel CPUs fell to just 20,000 in January-April this year, after 289,000 CPUs were imported in the same period last year. The figures were cited by an industry insider from unpublished Russian customs data. Another industry expert links the decline to payment problems that arose after Chinese banks began blocking Russian payments for semiconductors.

The upcoming Russian trade data releases could be quite interesting. It is already clear that the US executive order of December 2023 was one of the most effective steps in recent sanctions policy. The pain for Russian companies is real, even if it is not yet possible to quantify it. It has become clear that transactions in yuan are not beyond the reach of US sanctions. What matters is not the currency used in a transaction, but the real economic interdependencies between China and the US. As long as these interdependencies are as strong as they are today, Chinese banks will avoid risky transactions with Russia when Washington threatens them with sanctions.