Will falling oil prices hurt Russia?

The Central Bank of Russia has very limited liquid reserves. It could not do much itself to support the ruble if export earnings collapse, but it could try to tap Russia's "shadow reserves".

Over the past 30 months, relatively high prices have given a big boost to Russia’s tax and export revenues. In normal times, Russia would have used this opportunity to build up its currency reserves. Instead, Russia relaxed its fiscal rules to finance the war in Ukraine. With most of Russia’s liquid pre-war reserves frozen by the G7, the central bank currently has very little to work with in a “rainy day” scenario.

Now the oil markets seem to be at a turning point. A low oil price would create two distinct problems for Russia: falling tax revenues and a deteriorating trade balance. I will mainly discuss the second one here, because I think it would be more significant initially.

How far does the price of oil have to fall before it becomes a problem? Russia planned its budget on the basis of an oil price of $71.3 per barrel. This price level could be considered comfortable for Russia. Because of Western sanctions, Russian exporters have to sell their oil at a significant discount. The price of “Brent minus $10” is a good reference point for what Russia is actually earning. But even taking this discount into account, the average this year has not been too far from $70. So far, so good (or bad, if you are hoping for economic problems in Russia).

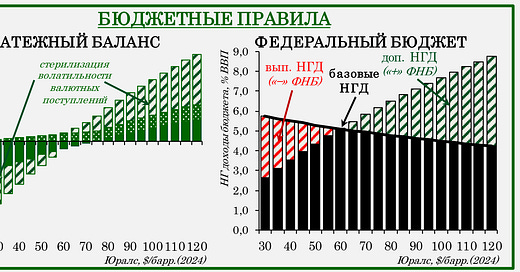

The Russian Ministry of Finance estimated the impact of different price levels on export revenues (left chart) and taxes (right chart) when preparing this year’s budget in the fall of 2023. As a general rule of thumb, Russia loses about 0.7% of GDP in tax revenues and about 1.5% of GDP in export revenues (or $25-30 billion per year) when the oil price falls by $10. For the oil price to become a serious problem for Russia, Brent prices would have to be closer to $50 for some time (currently, Brent is at $72), implying Russian prices of around $40 per barrel.

The sensitivity analysis conducted by the Ministry of Finance is probably incomplete. Oil and oil product exports account for about 50% of Russia’s export revenues, but unfortunately for Russia, the prices of the rest of its exports are closely correlated with oil: Prices for coal, gas, metals, ores, etc. are mostly driven up or down by the same factors, such as economic dynamics in China.

This correlation means that total Russian export revenue can swing up and down even more wildly than the analysis above suggests. In the last 15 years, export revenue has been going back and forth between 330 and 635 billion dollars. That is why it has been the policy of the Central Bank of Russia to build up currency reserves in good years and spend some in bad years, both to smooth the macroeconomic impact of these wild swings and to have a cushion in case of a severe downturn.

Russian Central Bank reserves

Before the full-scale invasion, Russia’s central bank reserves were worth 643 billion dollars. There has been some fluctuation in the total since then, but almost all of it has to do with exchange rates (the up and down after Feb. 2022 is a mirror image of dollar strength). In mid-August, the total was around 610 billion dollars.

But not all reserves are created equal: some are liquid and could help in an acute crisis, others not so much. For example, Russia’s gold reserves, estimated at $180 billion or 30% of total reserves, cannot be sold quickly - if Russia can find a way to sell them at all, despite sanctions on Russian gold and the central bank.

Russia’s holdings in Western currencies used to be the most liquid part of its reserves before 2022: dollars, euros, yen - about $300 billion, or almost half of the total. But this part is frozen and cannot be used by the Central Bank due to sanctions.

That leaves Russia with around 100 billion dollars worth of Chinese renminbi. This is not really a comforting cushion, even for a country with a structural current account surplus such as Russia. The macroeconomic survey of Russia’s Central Bank expects the total Russian import bill to range between 369 and 409 billion dollars in 2024-2027.

In the event of a sharp decline in the price of oil, export revenues may not be sufficient to cover Russia’s import bill. Imports could then be financed in other ways: For example, the Bank of Russia could sell some of its renminbi reserves to Russian importers. This would happen automatically as part of Russia’s fiscal rule. But the renminbi reserves would not last very long, and the central bank would probably be reluctant to spend much of it, precisely because liquid reserves are already so low. At some point, the currency intervention mandated by the fiscal rule would be suspended.

This means that the ruble would be hit hard by falling export revenues: It would have to keep falling until imports became so expensive and unattractive that Russians would import less and the current account balance would be restored. The problem is that this process would be very painful for Russian consumers. Inflation - already very high due to Russian war spending and labor shortages - would rise even higher. Russia had a comparable episode of low oil prices and devaluation in 2014-2017, and it was a big blow to real incomes. The Kremlin certainly wants to avoid a repeat of that at a time when it is fighting a major war.

In theory, Russia could try to borrow abroad in this scenario, and perhaps China could help out to some extent. But it is unlikely that this would be enough to solve Moscow’s problem and avoid a significant weakening of the ruble if the oil price stays low for an extended period of time. Instead, there may be another way, but it is a bit more complicated: Russia’s so-called “shadow reserves”. What are these shadow reserves, where do they come from, and how much are they?

Russian “shadow reserves”

One of the many interesting puzzles of Russia’s new post-sanctions economic reality is where Russia’s trade surpluses have gone over the past 2-3 years. In 2022, Russia recorded its highest current account surplus in history, mainly as a result of high energy prices and consequently high export revenues. A high current account surplus should go hand in hand with an accumulation of foreign assets by Russian residents (a short explanation of why is in the footnotes1). As shown above, central bank reserves have not increased. But where did the money go if it was not spent on imports and not added to reserves?

Russia’s balance-of-payments data shows a significant increase in assets held by Russian residents in one specific category. In the chart below, these assets are shown in dark green. They are part of “Other investment”, meaning they are not FDI, portfolio investment, central bank reserves or derivatives.

Russian data shows a strong increase in two subcategories of “Other investment”: “Loans, currency and deposits” and “Other accounts receivable”. The data also tells us that the assets are not held by government, banks or the Central Bank, and that they are short-term (rather liquid) investments. The value of these assets grew from 190 billion dollars to 370 billion dollars since the start of the full-scale invasion.

In a commentary for Brookings in April 2024, Gian Maria Milesi-Ferretti and Alexander Conner looked at available data from the IMF and the BIS and concluded that

“these assets appear to be mostly in the form of deposits and trade credits, and are held in countries outside advanced economies and the main global financial centers”

It is not entirely clear in which countries these assets are located or in what currencies they are denominated. However, since the assets are not visible in Western mirror statistics, they are likely to be held in non-Western countries. Russia’s extremely large trade surpluses with Turkey ($3 billion per month) and India ($5-6 billion per month) could be one of the reasons.2 In the words of the authors:

“The evidence suggests that Russia has accumulated increased claims on emerging economies, with an increased share of claims denominated in currencies other than those of the main advanced economies. These claims are likely to be less liquid than deposits in the main international banks (absent sanctions), but a more comprehensive assessment is difficult, since data on the relative size and location of such claims remains elusive.”

The issue of Russian “shadow reserves” was also discussed Benjamin Hilgenstock, Elina Ribakova and Guntram Wolff in an Intereconomics paper last year.

Could the Russian Central Bank deploy the shadow reserves?

The key question for Russia’s resilience to an oil price shock is how liquid the shadow reserves are - and how much control Moscow has over them. Can they be mobilized and sold for rubles when needed? Unfortunately, the answer is not entirely clear. But it is likely that the Central Bank would try. Over the past two years, the Russian government has experimented with rules on foreign exchange earnings, requiring exporting companies to convert a certain portion of their earnings into rubles. It may tighten these rules and try to force Russian companies to bring back some of these deposits.

In some cases, this may not be possible because deposits and trade credits may not be easily convertible. Much has been written and said about Russian export earnings “stuck” in Indian rupees. It is not clear how much this is (since some Russian-Indian trade is also conducted in dollars), but it could mean that Russian companies can only use their deposits to buy and import Indian export goods, most of which they don’t want or need. Although Russian imports from India have increased recently, they are still less than a tenth of Russian exports to India, and even with much lower oil prices, Russia will keep its trade surplus there.3

This means that Russia’s “shadow reserves” are a far cry from the insurance policy that central bank reserves in Western currencies used to be. Bringing them home will be a complex task and probably only partially successful. As a consequence of Western sanctions on Russian reserve assets and Russian spending on the war, Russia is not well prepared for a scenario of “lower oil prices for longer”. The result would be a significant devaluation of the ruble, leading to high inflation. In this scenario, real incomes, which have risen significantly since the start of the full-scale invasion and have led to much economic optimism among the Russian population, would take a painful hit.

This dependency is easiest explained if we break it down to the level of a company: Image a Russian firm that sells (exports) oil to China and also buys (imports) goods from China, such as machinery. When it exports oil, Chinese clients send renminbi to the firm’s account. When it imports machinery, renminbi are withdrawn from its account.

If the world market price for oil suddenly goes up a lot, Chinese clients will send much more renminbi on the Russian firm’s account, much more than the Russian firm needs to buy its machinery. As a result, renminbi will start to accumulate on the Russian firm’s account. The firm now has its own “trade surplus”. At the same time it is de facto accumulating assets in China - the increasing deposit on its account. In a way, it is “investing” in China with its increasing renminbi balance. This is why the firm’s individual trade surplus is also its own capital outflow.

In this sense, the Russian economy can be seen as one big firm that keeps accumulating foreign currencies on its accounts because it is exporting more than it is importing. In the past, the Russian Central Bank would go to that Russian firm, buy the renminbi from it and give the firm rubles. The firm would use these rubles to invest in Russia, pay dividends etc., while the Central Bank would stash the renminbi away, increasing its reserve assets.

However, nowadays the Russian Central Bank is not buying. It cannot buy the “toxic” foreign assets, and it does not buy much renminbi right now. The difference between pre-2022 and now is that the cut-off price of the Russian fiscal rule was changed from 40 dollars (plus dollar inflation) to 60 dollars to help the state finance the war. This means that it takes much higher prices before the Russian Central Bank starts buying foreign exchange from Russian businesses to increase its reserves.

So the Russian businesses are stuck with their surplus in foreign exchange revenue. This can clearly be seen in Russia’s balance of payments: Russian firms have accumulated enormous amounts of short-term foreign assets, mostly deposits, over the past two years.

Data on Russian trade balances with partner countries can be compared with Bruegel’s Russian foreign trade tracker.

In June 2024, Russian exports to India were 6 billion dollars, while imports from India were 0.5 billion dollars, according to Bruegel’s Russian foreign trade tracker.

Fascinating! I wonder whether Trump’s promised tariffs — which will hurt the U.S. asymmetrically, even as they hurt China — will prevent renminbi from flowing out of the Celestial Empire.