Money talks: Russian recruitment takes off after bonus hikes

Many Russian regions have dramatically increased their sign-on bonuses over the past year. Regional budget data says it's working.

Regional governments play a key role in Russia’s recruitment efforts. In order to attract more men to the army, many Russian regions have begun offering huge sign-on bonuses to recruits. The regional bonuses are paid on top of the federal incentive, which is currently 400,000 rubles. According to the Russian website Gogov, the highest regional incentive is offered in Samara and amounts to 3.6 million rubles. The total bonus (3.6 million from the regional government plus 400,000 from the federal government) is equal to 5 years (!) average salary and enough to buy a 2-bedroom apartment in the city.

There has been no comparable increase in the monthly salaries of soldiers, compensation for injuries, or payments to the families of killed soldiers. Russian officials have apparently concluded that a huge upfront payment is the strongest and most effective incentive. Still, regional governments also offer other benefits to the families of recruits: Free hot meals for children at school, privileged access to summer camps, debt relief, connecting the recruit’s house to the gas network etc. Some regions also pay bonuses directly to the relatives of recruits - apparently for their help in convincing a son/husband/father to go to war. Cynically, joining the military is presented as the best thing you can do for your family.

Russia still publishes a lot of regional budget data (on budget.gov.ru) and in some regions the spending on bonuses can be tracked. In theory, this data can be used to estimate the number of recruits in the regions. The great team at iStories has pioneered this approach using federal spending data. Using their methodology, I have analysed federal spending for the second quarter and the third quarter on this blog as well.1 The result indicated a slowdown of recruitment over the summer, which the regional data seems to confirm. Federal data for the fourth quarter has not been released yet.

iStories also looked at regional budgets in November, but focused on the burdon on budgets and less on recruitment success. Still, it helped me know which regional budgets were worth analyzing - so I owe them a big thank you. For this blog post, I analyzed spending on recruitment in roughly 20 Russian regions (more to come) over the last year. Below, I will present some preliminary conclusions from that analysis. It’s important to take everything here with a grain of salt: This is a new approach and there are lots of uncertainties. It is work-in-progress (there will hopefully be more blog posts based on this data). I could write 10 paragraphs of disclaimers - maybe later.

Recruitment in Q4 of 2024 accelerated significantly

Spending on recruitment has accelerated strongly in all regions I have analyzed so far. Of course, some of this increase is due to hikes of the regional sign-on bonuses. But if you divide the spending on bonuses by the bonus size at the time of spending2, indicating the number of bonuses paid out, the result is still a strong increase. This indicates that more men were recruited.

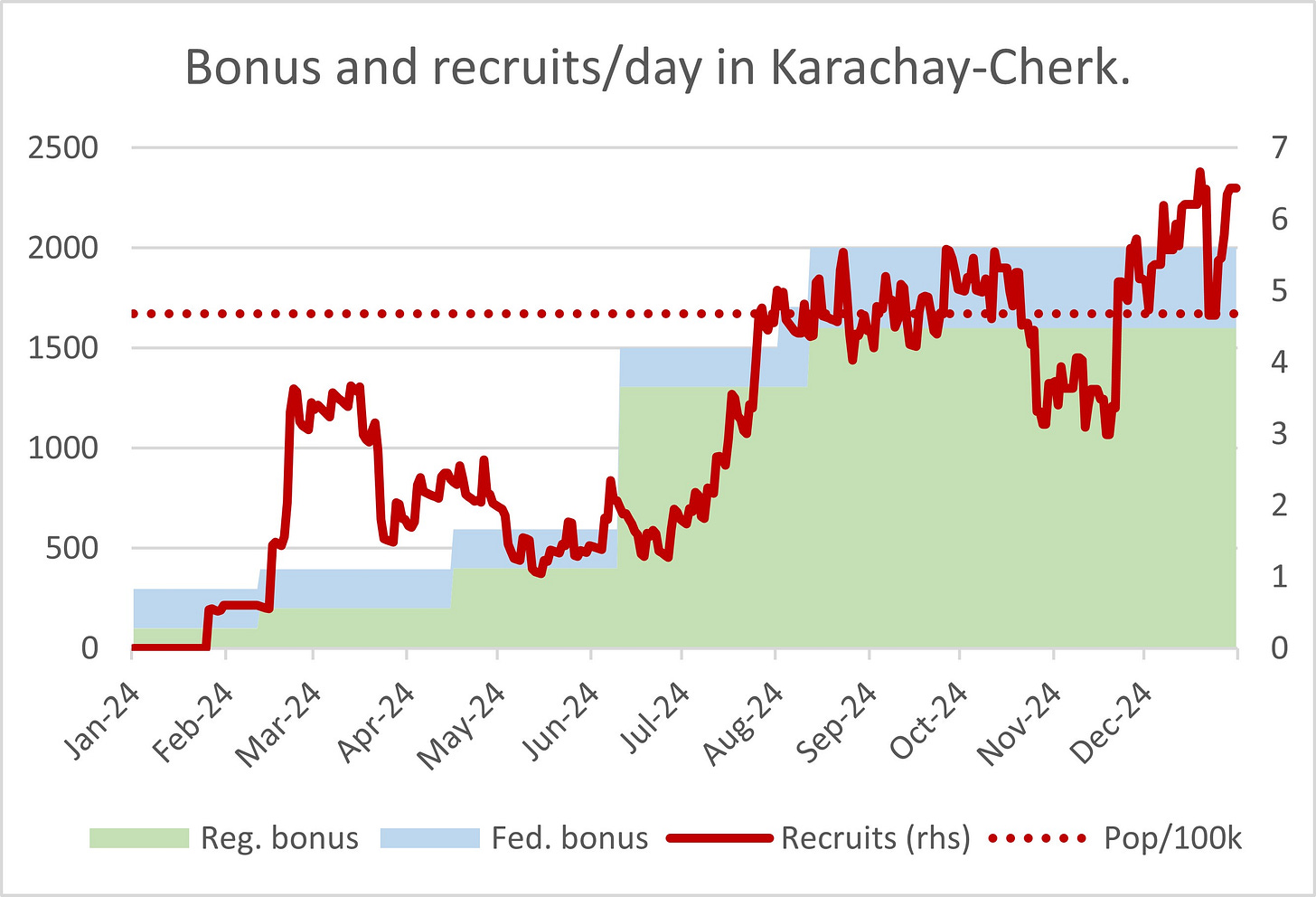

In the following charts, the green area is the regional bonus, the blue area is the federal bonus (in 1,000 rubles, left axis). The estimated number of recruits per day is the red line (right axis). The dotted line is the regional population divided by 100,000 - more on this later. My first example here is Tomsk Oblast. Estimated recruitment was relatively low in the first half of the year (5-10 per day), but accelerated to 15-20 per day in autumn. The regional bonus only increased once from 300,000 to 400,000 rubles, on August 1, the same day the federal bonus was increased from 195,000 to 400,000 rubles.

I want to address one important counterargument to these findings up front: There are always seasonal patterns in budget spending. For example, almost all public budgets spend a lot in December. However, this probably does not have much impact on the payment of recruitment bonuses, which have to be paid within a certain number of days after the contract is signed (the maximum delay is limited by law). In addition, there were regions that did not see a significant increase in bonus spending in December. Finally, early data from January/February 2025 as well as some data from late 2023 indicates that the seasonal pattern is not as strong as - for example - in public procurement.

Higher bonuses are working

There are some extreme cases of bonus increases in some Russian regions that make it possible to analyze the response of recruits to the changing incentives. It is important to keep in mind that bonuses are not the only factor influencing the decision to sign a contract: There are also other benefits, there is the federal bonus, and there are individual risk calculations (if you expect the war to end soon, you sign up now, if you expect the bonus to increase much more in the future, you wait…). There are also incentive payments on the municipal level (they tend to be small compared to regional bonuses).

However, if the bonus goes up by millions of rubles, recruitment usually follows. Here is an extreme example from Karachay-Cherkessia: The regional bonus was raised to 1.6 million rubles, while the average monthly salary in the region is 45,000 rubles.

By now, it is also clear that the data is pretty messy: Spending tends to begin in late January, then it has to “catch up” (is rather high initially), and it can be quite chunky. But it still contains valuable information.

The rate of recruitment is similar across regions

Analyzing the data, I noticed that the daily recruitment rates in the last quarter of 2024 were fairly proportional to the population size of each region. This was relatively consistent across small regions, large regions, wealthy regions, so-called ethnic and non-ethnic regions etc. Unfortunately, I don’t have data for the “usual suspects” of heavy recruitment, such as Buryatia. Nevertheless, the pattern is still remarkable.

This is why I added the dotted line to the charts: It is the region’s population divided by 100,000. It is really close to the daily recruitment rates in the fourth quarter of 2024. For example, this is Moscow Oblast, the second largest region in Russia (over 8 million population), and also one of the richest (average salary around 100,000). The data is particularly messy because of two big jumps in spending in April and July.

Another example, this time from the Urals industrial part of Russia, is Sverdlovsk Oblast (4.2 million population and 80,000 rubles average salary).

Regions with lower recruitment per capita tend to increase their bonus

The bonus a region offers is a pretty good indication for how recruitment is going - relative to the regional population. Karachay-Cherkessia (above) is one example of very high bonuses, as is Sverdlovsk. But there is also the opposite: Regions that did not increase bonuses on their own at all. There are also other explanations why some regions may have increased bonuses and others didn’t (for example: available funds). But recruitment success relative to population seems to be the most consistent explanation so far.

When Putin raised the federal bonus to 400,000 rubles in August 2024, all regions were told to at least match that figure, and they all did (except for Chechnya, apparently, but Chechnya always has its own rules). Several regions with successful recruiting - relative to population - stuck to that mandatory minimum. One of them is shown above: Tomsk Oblast. You may have noted that recruitment in Tomsk far exceeds other regions relative to population. Another example - also from Siberia - is Krasnoyarsk Krai:

The Kremlin may have set a recruitment rate based on regional population

Again, the results above are preliminary and the project is work-in-progress, and I realize that I may have provided too few examples so far. Still, the patterns described hold true for most regions I looked at so far. This could indicate that the Kremlin is telling the regions to achieve a certain level of recruitment based on their population - and the regions are using the regional payout as the main instrument to fulfil Moscow’s requirements. The data suggests that the desired daily rate of recruitment is somewhere around a region’s population divided by 100,000.

Extrapolated to all of Russia (144 million population), this would means around 1,440 recruits per day for all of Russia. Towards the end of the year, it appears that many Russian regions have met their target, indicating a strong increase in recruitment across Russia in the fourth quarter. In a few weeks, federal budget data will be released and hopefully tell us more about the big picture.

Analysing the federal data had several advantages: 1.) it covers all of Russia, so the data is relevant on the macro level, 2.) the federal bonus was relatively constant (changed only once), making it easier to derive the number of recruits from total spending, and 3.) the system of payouts is relatively clear, while regions often have several overlapping schemes that frequently change. But there were also many problems and unknowns with the federal budget because the data is only available on a quarterly basis: Is the spending influence by seasonal patterns that have nothing to do with recruitment success? How long does it take until an increase in the bonus leads to higher budget spending? How effective is a higher bonus for recruitment?

The analysis has shown that there is usually a lag between bonus hikes and increased spending of up to 2 months. To account for this, spending was divided by the average bonus of the previous 60 days when estimating the number of recruits. For example, if the bonus increased from 400 to 800 thousand rubles, the average bonus paid was assumed to be 600 thousand one month later and 800 thousand two months later. Because spending happens in chunks (often weekly, but not always), the calculation uses the average spending on bonuses of the previous 30 days.

Very interesting analysis and thought process. If we take your number (last paragraph), it means you are suggesting roughly 50k recruits are called upon per months or half a million more or less yearly. Plausible ?